By Sam Feliciano

ELIGHTENMENT AND ILLUMINATION

Vienna in the 18th century was a meeting place for great thinkers and artists alike. The enlightenment was well underway by the 1780s, and there was a new hope for the future of mankind. Also called the “Age of Reason”, the “Enlightenment” was typified by a new attitude where reason was seen as the source of authority. Even in mainstream historical records, the influence of speculative freemasonry on the Enlightenment is tangible. This was also complemented in freemasonry by a new spirit of freedom blossoming in the lodges all throughout the known globe. Individuality and rebellion was rampant, even in the universities. To quote the Catholic encyclopedia:

“After the founding of the Bavarian Academy of Science at Munich in 1759, an anti-ecclesiastical tendency sprang up at Ingolstadt [university] and found an ardent supporter in Joseph Adam, Baron of Ickstatt, whom the elector had placed at the head of the university. Plans, moreover, were set on foot to have the university of the third centenary the Society of Jesus… suppressed, but some of the ex-Jesuits retained their professorships for a while longer. A movement was inaugurated in 1772 by Adam Weishaupt, professor of canon law, with a view to securing the triumph of the rationalistic “enlightenment” in Church and State by means of the secret society of “Illuminati”, which he founded.” [1.]

In 1774, Adam Weishaupt started bringing his ideas to the lodges of freemasonry. Allegedly, Weishaupt was unimpressed and resolved to start a new secret society within freemasonry, which would most effectively realize the illuminist goals. Through secrecy, the new order could “at all times be precisely adapted to the needs of the age and local conditions.”

Weishaupt held a professorship at Ingolstadt University during the Enlightenment, and is described by his contemporaries as a rather antagonistic fellow, more interested in theory and thought than action. This description is reflected in the history as well, for it took the addition of prominent freemason Freiherr von Knigge in 1780 for the Illuminati to make any real progress. Although Weishaupt MAY have started the Illuminati, in truth it was in concept only. Knigge was easily it’s true father; developing the degrees of the Illuminati, and ultimately being responsible for the majority of it’s promotion. Within two years of Knigge’s influence, the Illuminati’s membership grew swiftly to 500 members.

In 1782, Knigge and Weishaupt proudly proclaimed their “Illuminated

Freemasonry” to be the only “pure” freemasonry. Soon thereafter, the addition of Johann “Amelius” Bode, gained the new order credibility. The movement quickly became the newest, coolest, most exclusive secret society around. This Illuminati fever spread throughout the world, gaining footholds in Sweden, Denmark, Hungary, Russia, Poland, Austria, and France. The order’s number grew to approximately 2000 at its peak, enticing many of the most prominent members of the “enlightenment” to illuminism, such as Goethe, Herder, and Nicolai. All was not well within the inner circle, however. Returning to the Catholic Encyclopedia:

“…But in 1783 dissensions arose between Knigge and Weishaupt, which resulted in the final withdrawal of the former on 1 July, 1784. Knigge could no longer endure Weishaupt’s pedantic domineering, which frequently assumed offensive forms. He accused Weishaupt of “Jesuitism”, and suspected him of being “a Jesuit in disguise” (Nachtr., I, 129). ‘And was I’, he adds, ‘to labour under his banner for mankind, to lead men under the yoke of so stiff-necked a fellow?–Never!’

“Moreover, in 1783 the anarchistic tendencies of the order provoked public denunciations which led, in 1784, to interference on the part of the Bavarian Government. As the activity of the Illuminati still continued, four successive enactments were issued against them (22 June, 1784; 2 March, and 16 August, 1785; and 16 August, 1787), in the last of which recruiting for the order as forbidden under penalty of death. These measures put an end to the corporate existence of the order in Bavaria, and, as a result of the publication, in 1786, of its degrees and of other documents concerning it–for the most part of a rather compromising nature–its further extension outside Bavaria became impossible. The spread of the spirit of the Illuminati, which coincided substantially with the general teachings of the ‘enlightenment’, especially that of France, was rather accelerated than retarded by the persecution in Bavaria.” [2.]

Although Elector Karl Theodore famously made Illuminati membership illegal, it seems that Knigge and Bode were already trying to neutralize Weishaupt, and ideally make the Illuminati even more exclusive and secretive. By making the promotion of Illuminati illegal, Karl Theodore may have unintentionally (or even possibly intentionally) done the Illuminati one of the best favors a secret organization could ever ask for, easily making them stronger. This is especially true when considering that the Illuminati was already a worldwide organization, and the state of Bavaria was ultimately only one state in one country; Germany.

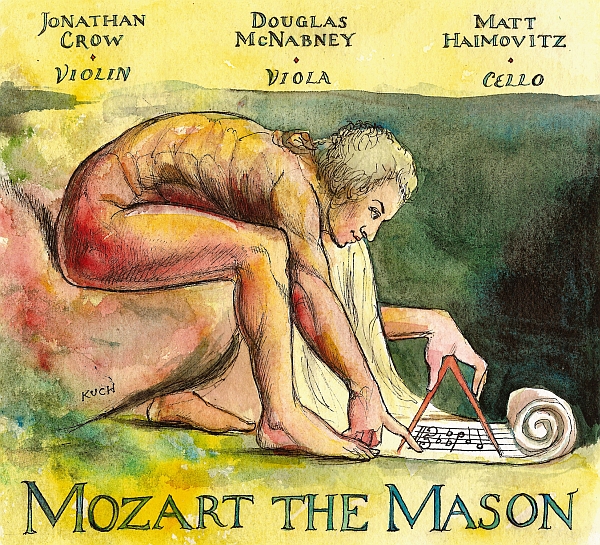

MOZART’S INITIATION

As was outlined earlier, most of the main movers and shakers of the enlightenment period were usually affiliated with freemasonry, or the Illuminati, or both. Because of the animosity brewing against secret societies in Munich, many members went out of their way to cover up their connections to the order.

The public paranoia being paramount to fear, being discovered as a current or former member of the illuminati could potentially spell trouble. As a result, many members burned records of their affiliation with freemasonry and Illuminati.

One such famous freemason of the enlightenment who covered up his connection to the order was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Although Mozart was absolutely surrounded by freemasons and illuminati members most of his later life, Mozart never openly admitted his involvement in the Masonry. This search is further complicated because when the animosity toward the Illuminati was brewing in Munich, it seems that Mozart’s family covered up and burned much of the corroborating evidence from his own personal files.

How then do we know that he was a freemason? Despite no personal records of his admittance, there is a bounty of evidence within the lodge available. As early as 1783, both Wolfgang and his father Leopold were Visiting Members of the “Eclectic Lodge” in Salzburg. At the time, there were also two other active Illuminati lodges in Salzburg; the “Apollo” and “Knowledge” lodges. A few years after, we have his initiation into the lodge “Zur Wohltatigkeit” (charity) on Dec 14, 1784 in their own records. It seems he had been suggested on December 5, and was #20 in the lodge register. A few weeks later, Mozart was passed to his second degree at “Zur wahren Eintracht” (true harmony) lodge on the following Jan 7, 1785 (at the request of his mother lodge “Zur Wohltatigkeit”). Another curiosity appears in the records as well. Apparently, Haydn was also initiated into this lodge the following meeting. [3.]

Soon after his initiation in 1784, Mozart even makes a special request that his father be admitted shortly thereafter. The lodges oblige, and Leopold is initiated. According to Nettl, this was an attempt on Wolgang’s part to bring them closer. Mozart’s relationship with his father had been dwindling ever since Wolfgang’s marriage to Constanze Weber. Ultimately, their common bond through freemasonry did not change his father’s disapproval.

MOZART’S FRIENDS

Although Mozart struggled with his health throughout his life, the conditions surrounding his death are mysterious at best, and famously alive with rumor. In 1791, despite being able to conduct the premier on Sep. 30 of what proved to be his final Opera, The Magic Flute, Mozart’s health plummeted shortly thereafter.

On Dec. 5th 1791, at 1am, Mozart died. In Niemetschek’s biography, he describes Mozart’s feelings about his illness as related by his wife, Constanze:

“On his return to Vienna, his indisposition increased visibly and made him gloomily depressed. His wife was truly distressed over this. One day when she was driving in the Prater with him, to give him a little distraction and amusement, and they were sitting by themselves, Mozart began to speak of death, and declared that he was writing the Requiem for himself. Tears came to the eyes of the sensitive man: ‘I feel definitely,’ he continued, ‘that I will not last much longer; I am sure I have been poisoned. I cannot rid myself of this idea.’” [4.]

The tragedy of Mozart’s death was that his career was only just stabilizing. Although he was famous, Mozart struggled financially for most of his life. In his final year, the commissions of wealthy noblemen implied that Mozart was on the brink of financial security. As well, Mozart’s new (and final) Opera, The Magic Flute, was starting to gain popularity throughout Europe.

The Academy Award winning film “Amadeus” [5.] makes the claim that Salieri killed Mozart out of jealousy over his talent. I find this an interesting theory to emerge in the mainstream, mainly because Salieri was one of Mozart’s only five friends to actually attend his funeral, along with family. Also, his body was buried in a mass grave (very unbecoming of a Mason) at the behest of his friend Baron Gottfried van Swieten. Not to mention, Salieri has no known Masonic connections.

What I do find suspicious is the seeming absence of the fraternity as soon as Mozart fell ill, especially when considering Mozart’s Masonic involvement toward the end of his life. Although his Masonic attendance seems to have diminished in the records, Mozart was still was very close with many prominent masons right up until his illness. Many of Mozart’s closest friends, as well as librettists and financiers were prominent masons. For example, freemason Lorenzo da Ponte wrote the libretto to 3 of Mozart’s works, including Don Giovanni and the Marriage of Figaro, both plays very rich in Masonic symbology.

In fact, when one views Mozart’s work following his initiation in 1984, all of it carries prominent Masonic symbology, and strong undertones of Luciferian philosophy. In George Bernard Shaw’s “Man and Superman”, he famously interprets Don Giovanni as a story of a Satanic being who challenges God.

Mozart’s final play, the Magic Flute, is certainly one of Mozart’s most Masonic. Many historians and critics have tried to break down the symbolism of this play as a metaphor for the enlightenment movement. Even by their own admission, these interpretations are incomplete. For anyone familiar with the mystery religion, however, the meaning is clear. If you read into the deeper symbolism and how it relates to Masonic philosophy, a darker story emerges. To be sure, the Magic Flute is an allegory referencing the accomplishment of the soul by the initiate of the mysteries, and the crowning of Lucifer as king over the wild superstitions of the human mind.

THE MAGIC FLUTE; ACT 1

The Magic Flute’s main character, Tamino, is symbolic of human consciousness, or the initiate. The story opens with Tamino being pursued by a serpent (the intellect/ divine wisdom). The Queen of the Night (the reigning monarchy/ G-D) and her three women (superstition, fear, and ignorance/ the church, the state, and the mob) come and kill the serpent. Tamino awakens and finds the snake dead, and meets a feathered man named Papageno (the body). Papageno quickly claims to Tamino that he saved him from the serpent. The three women then appear and lock Papageno’s mouth for the lie, explaining that they and the Queen of the Night rescued Tamino.

The Queen of the Night (G-d) then commissions Tamino to kill her adversary, Sarastro (Lucifer), who has taken her daughter, Pamina (the soul), captive in his castle. The Queen claims that Tamino must kill Sarastro to win the hand of her daughter. The three ladies give Tamino a magic flute (the creative force/ the penis of Osiris), remove the lock from Papageno’s mouth, and give him magic bells (the receptive force/ feminine) to protect him. Papageno is then ordered to quest with Tamino to rescue her daughter. Three spirits (the trinity) then guide them to Sarastro’s temple, where they will find and rescue Pamina.

Papageno goes ahead of Tamino to find Pamina. At Sarastro’s temple, Papageno finds a black man named Monostatos (Satan/ the persistent question of uncertainty) who is holding Pamina captive. She is told of Tamino’s quest, and eagerly awaits her rescue. When Tamino gets to the temple, there are three entrances. He is turned away from two of them, but when he arrives the third entrance, he finds a priest. This priest then explains to Tamino that Sarastro is benevolent, and not evil, as he had been led to believe. Tamino tries his magic flute, and Papageno plays his pipes in response, leading Tamino to Pamina.

When Tamino and Pamina meet, Monostatos and his followers take them captive, but then Papageno is able to enchant them with his magic bells and save the young couple. When Sarastros arrives, Tamino asks Pamina what to do, and Pamina tells Tamino to tell the truth. As it turns out, Sarastros is sympathetic to the young couple, and rebukes Monostatos for his lustful intentions with Pamina. The couple is then led to the Temple of Ordeal, where a complete Masonic ritual takes place, overseen by the priests of the Temple of Isis and Osiris.

CONCLUSION

I will not break down the symbology of the second act of the Magic Flute or you, only because I want you to go and investigate it for yourself. I assure you; it will be enough to put your jaw on the floor. There is no question about the Masonic influence on the Magic Flute [6.]. However, in light of this, if there is any question as to whether or not the Masonic fraternity is a Luciferian religion, please take the Magic Flute into consideration. We may never know who killed Mozart, or why. Still, I submit the timing of Mozart’s death to this play as a curious coincidence.