Here’s an account of Texas as part of Mexico:

Texas remained an independent republic for almost a decade. Although Texas formally asked to become part of the United States, the American government hesitated. Mexico had made it clear that annexing Texas to the Union would be equivalent to the declaration of war. But on December 29, 1845, President John Tyler signed the bill to admit Texas to the Union as the last act of his administration. Mexico broke relations with the United States.

James K. Polk, who had strongly advocated annexation of Texas and expansionism in general, followed Tyler as President. Polk sent John Slidell, Minister of Mexico, to negotiate, offering to cancel a series of debts if Mexico recognized the Rio Grande as the border between the two countries. Slidell also tried to buy the territories of New Mexico and California.

In turn, Mexico asked the United States to reconsider annexing Texas if it admitted Slidell to negotiations. The United States refused, Mexico declined to talk with Slidell, and Polk ordered troops to the disputed border.

General Zachary Taylor with 4,000 men arrived near Corpus Christi along the Rio Grande in late January 1846. The Mexicans regarded it as an invasion of their territory and threatened to attack if the United States did not remove its troops.

The American troops stayed along the mouth of the Rio Grande, waiting for Mexico to begin hostilities to initiate the war. In April 1846, during a small encounter between American and Mexican troops, several American soldiers were killed. President Polk convened Congress and announced: “American blood has been shed on American soil.” The United States officially declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846.

The war lasted two years with the Mexican Army suffering huge losses. General Zachary Taylor’s forces moved south from Texas to capture Monterrey. On February 22, 1847, Taylor’s troops marched from Monterrey to Buena Vista and defeated Santa Anna’s men, who outnumbered the American force three to one.

I think it’s fair to point out that most accounts view the war as a racist land-grab by greedy Americans:

Since end of the U.S.-Mexican War, historians have been divided in their interpretations. Some have held the United States cupable. Others blame Mexico. Studies of the literature reveal the majority of writers have taken a balanced view, holding neither country entirely blameless. Despite the fact that there is no hard evidence to support their views, those who blame the U.S. claim that the war was a “shameless land-grab” brought on by the intrigues of President James K. Polk or that it was part of some sinister plot on the part of the so-called “Slavocracy” to extend slavery. These unfounded arguments are nothing new. They are the same ones used by nineteenth century Whig politicians in their attempts to discredit President Polk. The truth is more simple: The war was fought to defend the right of a free people, namely the citizens of the Republic of Texas, to determine their own destiny, that is to join the American union of states. This was a right that the government of Mexico sought to deny them.

Opposition to the war has often been exaggerated. Only a few outspoken Whig politicians, such as John Quincy Adams, were against it. At the time of the war another oft-cited critic, the writer Henry David Thoreau, was virtually unknown outside his hometown of Concord, Massachusetts. Most Americans enthusiastically supported the war. Approximately 75,000 men eagerly enlisted in volunteer regiments raised by the various states. Thousands more enlisted in the regular U.S. Army. There was no need for a draft. In some places, so many men flocked to recruiting stations that large numbers had to be turned away. Thousands of newly-arrived Irish and German immigrants also heeded the call to arms.

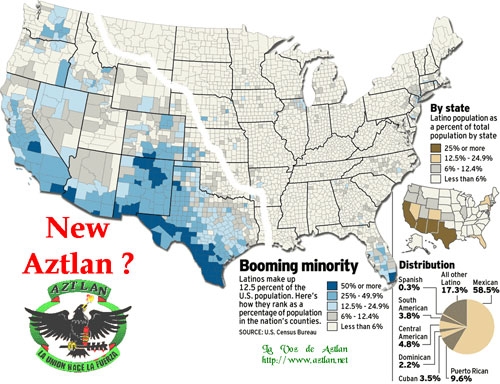

Groups that support the concept of Reconquista include the Mexica Movement and Voz de Aztlan.